Processing Stutters

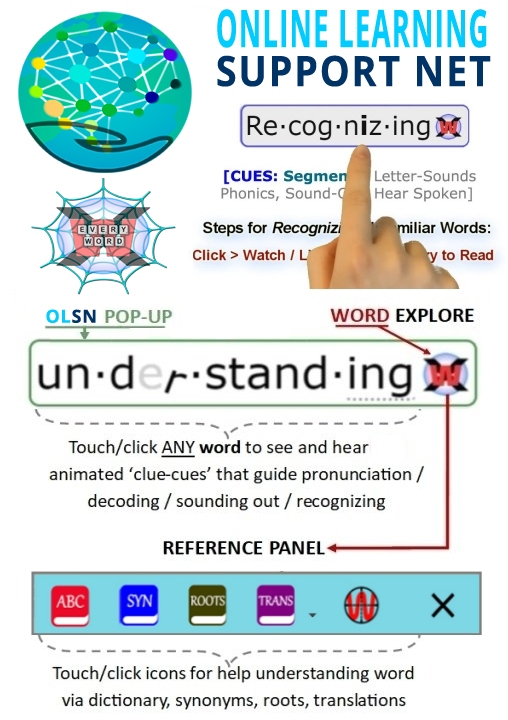

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Processing Stutters

David Boulton: It’s clear in talking to the phonological side of neuroscience that fuzzy representations in the phonemic, phonological dimensions require more processing time to disambiguate and cause a processing stutter – again purely on the auditory processing side.

To the extent that that’s true, then it seems equally true that the time it takes to disambiguate the code is also causing a processing stutter. This is one of the problems I have with terms like ‘alphabetic principal’ or ‘breaking the code’ because they over-simplify what we’d other wise call, more in the computer world so to speak, ‘disambiguation’, which is to take this stream of letters, some of who’s sound values depend on words that haven’t been read yet, buffer them up and construct these approximate word sounds from these fuzzy letter variables.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Right.

David Boulton: And that the more time it takes to do that, just at that level in this module we’ve been describing as the language simulator, then the more that module is not delivering the language stream in time for comprehension.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Yes, I think that’s right. Helen Osgoldand I wrote a chapter that I put in my 1985 book about this. We called it code asynchrony; the idea being that orthographic phonological and symantec codes that had high levels of skill come out all at once. And in low levels of skill there can be an asynchrony in a sense that you’re getting some of the graphemes and some of the phonemes but you’re not getting the whole thing yet and things get all out of phase. Instead of mutually strengthening each other so that at the end of the decoding episode you have a stronger word representation that’s accessible by orthography, you’ve got bits and pieces and only partial success.

Now what you’re adding to that idea. I think specifically what you are saying is if the phonological space is too fuzzy because the letter hasn’t made phonological differentiations that turn out to be relevant for English vocabulary then that’s going to be an additional problem. There’s not going to be a differentiated phonological coding that comes out of any given word reading event. Then the question is how that develops.

Some of the pre-literacy research on children’s development of spoken language, I think, is suggesting that fuzzy phonological representations are normal and characteristic of early language development and that they become less fuzzy, more differentiated and more articulate only in response to increasing demands in the linguistic environment, which usually amounts to having to learn a new word or having to distinguish a new word from one that you already have and that can force you to make new phonological distinctions.

I think the fuzziness is normal and I think what can happen with reading when things are working well is that getting good feedback, either internally generated or externally, on a decoding attempt can have the same effect, that is forcing phonological differentiation. So, you can say an approximation. It doesn’t map onto anything that you know and so you either get feedback that it’s actually this word rather than that word or that the word that you’re trying to decode is novel and has its form and that produces new phonological representation. That, I think, is an interesting possibility for understanding this in general.

David Boulton: Right. So, they’re feeding into each other. I think at one level we’re a fuzzy processor in a myriad of ways.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: I think you’re speaking formally, a formal idea of fuzziness, which is probabilistic category membership. That’s the formal sense.

David Boulton: Yes, but where I’m going with this is that to the extent that the time it takes to get from elemental recognition through disambiguation, through to an approximated word to move to recognition with… if that assembly takes too long then there’s a stutter that radiates through everything.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Right, because it turns out you’re actually not assembling a unit that you can then use as a representation. Things are too disconnected.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: I talked about this in terms of the theory of what it is that children learn to represent when they learn to read, something I called specificity representation. So that before acquiring specificity as a characteristic representation, I would put in these formal terms: it has variables instead of constance. Instead of always having this sound, it has sort of something like this sound or something like that sound.

David Boulton: It’s very much like a quantum wave collapsing to a particle in the context of the process.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Yeah, maybe. I haven’t thought about that. That’s an interesting way. Okay.

Charles Perfetti, Professor, Psychology & Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/perfetti.htm#ProcessingStutters

Reading Difficulties and Code Disambiguation Time

David Boulton: So, my point is that a significant percentage of the difficulty that most people face, at least in the United States with English, is connected to the time it’s taking the brain to work out the letter-sound correspondence fast enough to feed the assembly to comprehension before it stutters and drops out.

Dr. Zvia Breznitz: Absolutely right. Exactly. And we have some evidence, you know, when you look into the brain of beginning readers or the brain of a dyslexic you see similar kinds of phenomena as the brain is searching for the solution. You see a wider area of activation in the brain compared to a proficient reader or a normal reader or regular reader.

In the normal reader’s brain it is activating for only a short period of time in a very local brain area. It’s not spreading out activation and you can see that he is not looking for a solution. If you know exactly how to go and how to solve the problem you will become a good reader.

Zvia Breznitz, Director, Laboratory for Neurocognitive Research, University of Haifa. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/breznitz.htm#ReadingDifficultiesandCodeDisambiguationTime

The Gap Between Modality Speeds

Dr. Zvia Breznitz: Later on what we found out was that one of the reasons that the brain of the dyslexic doesn’t develop a total template of the word, of the phoneme grapheme correspondence, is because the reading basically relies on activity of the two modes: of the auditory or the auditory phonology and the visual orthography mode.

Now enter the integration between the two.

David Boulton: Yes, which is a lot more complex in different orthographies.

Dr. Zvia Breznitz: Absolutely. Basically, whether we are talking about Hebrew, Arabic or Semitic languages or any of the Romance languages, basically you have to see the symbols of the printed material and you have to make some kind of acoustic representation of them. So, it can be any language. The matching between the visual symbol and the acoustic phonological one does not only rely on the accuracy of the correspondence but also on the time it takes both modalities to process the information.

David Boulton: Right. And so it takes time even in a purely phonetic system to get the association between the visual and the auditory, and then in a non-phonetic system, where there is a greater context dependant variation in the sound value that accompanies a letter, there is more processing time involved to associate those two correctly.

Dr. Zvia Breznitz: Exactly. Now, we know from neurobiology one modality is processing information on a different time schedule than the other one. We know that what really affects the process is the gap between the processing speed of the two modalities.A larger gap, like what we found among the dyslexic readers, doesn’t effectuate appropriate matching between the sound and the visual symbol. It doesn’t allow it. It causes a mismatch.

David Boulton: It goes too slow for the stream to cohere.

Dr. Zvia Breznitz: Exactly. Because everything has to be fast enough because you are processing information within the limitations of the information processing system.

So, there is a fading out in the auditory memory in the place where it has to be matched because one modality is processing at a faster speed compared to the other one. So the effect of an inappropriate template being stored is the gap or what we call asynchrony.

Zvia Breznitz, Director, Laboratory for Neurocognitive Research, University of Haifa. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/breznitz.htm#TwoModes

Building Blocks of Reading

David Boulton: So, one of the critical building blocks is the ability to recognize differences in sound, in time. In the technology world we would call it the ‘analog to digital converter’ where the sound stream is sliced into digital chunks. If the child’s brain is not doing it fast enough then they won’t have the granularity of distinction necessary to build reading upon.

Then once they have that, there’s a minimum frequency rate or speed of processing that is critical to assembling the virtually heard or actually spoken stream. Any one of these things can cause a bog in processing which causes the stutter that breaks down reading.

Dr. Paula Tallal: Absolutely. Right. I hope we can put your words in there, that sounded perfect. That was very good. You certainly got it. You certainly have the hypothesis.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#BuildingBlocksofReading

Not Much of a Fault

Dr. Michael Merzenich: I mean, you wouldn’t have to have much of a fault in this machine operating with high speed in this incredible processing efficiency that’s required to begin to see somebody be a little slower at it or a lot slower at it. And so therefore, dyslexia, in a self-organizing machine of this nature, is an expected problem. It’s an expected weakness. It should apply very widely.

David Boulton: In addition to the underlying sound processing issues we talked about earlier, wouldn’t the trouble also be related to the confusion in correspondence between letters and sounds? That the more brain time it takes to resolve the ambiguity…

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Absolutely .

David Boulton: The greater the stress on the system to produce…

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Make the representation of the sound parts of words a little fuzzy and it’s going to slow down the ability. And as soon as you do you also have a decline in processing efficiency, the ability to hear something and rapidly translate it or to do anything with it has slowed down.

David Boulton: Doesn’t that same exact argument apply to the fuzziness between sounds and letters?

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Absolutely it does.

David Boulton: That’s a technological artifact not a naturally occurring sound scape variation. That’s my point.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Yes, absolutely. Yes, it is in a sense a technological artifact. Absolutely.

Michael Merzenich, Chair of Otolaryngology at the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences at the University of California at San Francisco. He is a scientist and educator, and founder of Scientific Learning Corporation and Posit Science Corporation. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/merzenich.htm#NotMuchofAfault

Automatization

I think the crucial problem with all of language as we use it today is the problem with automatization. How do we take something that has so many variables, so many possible connections and combinatorial options, and do it without having to think about it? How do we turn this complicated set of relationships into a skill, ultimately, that can be run, in effect, as though it was a computation?

What we’re really doing is we’re taking something that is a nightmare for computation and as we mature both as language users but also as readers and writers, we have to automatize it so we don’t have to think about those details. The problem with automatization is that at any step, if you’ve got a slowdown step, if any piece of that enterprise has a block, where you can’t hold enough of the information, the whole house of cards falls apart. You can’t build beyond that point.

It looks as though, with the acquisition of language itself, speech particularly, that we’ve got a lot of redundancy in the system. We have work arounds that are there, probably evolved there, because it was so important and because there was enough evolutionary time behind that process to build in that safety net. With respect to reading and writing, there was no evolutionary support. With respect to reading and writing, there is no safety net. There are probably very few redundant work arounds that are successful that don’t take longer, that aren’t more clumsy – aren’t so clumsy that they drop something, they don’t keep track of it, or they’re simply too slow to keep up with your memory process.

David Boulton: Right. We stutter.

Dr. Terrence Deacon: Right.

David Boulton: We stutter and when the stutter happens during this assembly, you get this start-stop hesitation that after a while creates this frustration and reading aversion and all that can go with it.

Dr. Terrence Deacon: Right.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#Automatization

Missing Scaffolding

What we do learn, as in any other perceptual task, is what kinds of things go together and that makes life much easier for us. So when you look at the older kids who are getting that wonderful expression of yours, ‘mind stutter,’ they don’t have the patterns built, they don’t have enough orthographic substructure, infrastructure, to do the automatic processing. The word is not in their vocabulary, so they don’t get the full duplex out, when they kind of sound it out, and nothing comes back.

Marilyn Jager Adams, Chief Scientist of Soliloquy Learning, Inc., Author of Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning About Print. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/adams.htm#EyeMovements

Articulation Stutters and Code Ambiguity

David Boulton: The hesitation, the slow processing that we were talking about before…

Dr. Reid Lyon: Yeah, yeah.

David Boulton: Seems to correspond to the ambiguity. In other words, if you track a child’s articulation…

Dr. Reid Lyon: Yeah.

David Boulton: As they’re flowing through the reading stream you can see the bog happen in direct correspondence to the code’s knots.

Dr. Reid Lyon: You can, you can. Absolutely. This underscores the need for teachers to know where the ambiguities are…

David Boulton: Right.

Dr. Reid Lyon: To know the sequences that are most efficient to move kids to mastery. If you look at the instructional programs that are most beneficial for kids at risk, that really do get swallowed up by this ambiguity, those instructional programs carry a sequence of presentation designed to move kids systematically…

David Boulton: But it’s statistical, probabilistic cannon fire, rather than trying to get into sync with the child and bring them right to the edge of the ambiguity so that they are actually stuttering, stumbling right there and then helping them learn through it.

G. Reid Lyon, Past- Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Current senior vice president for research and evaluation with Best Associates. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lyon.htm#stutterscodeambiguity

Correspondence Between Articulation Stutters and the Code

David Boulton: One of the things that we notice is there is a very definitive, first-person, observable correspondence between the articulation stutters of a struggling reader and the code confusion that they’re actually encountering at that part of the stream of reading.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Oh, no doubt about it.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#BrainCapacitySpeedofProcessing