Self-Esteem and Shame

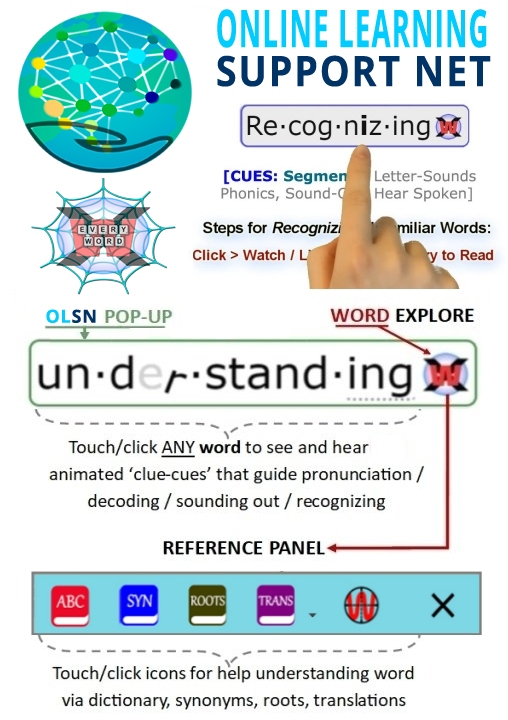

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

The Real Cost is Lost Self-Esteem

I think the main thing to emphasize for anyone who has worked with a child or with an adult who has a reading problem, either who is low literate or is just struggling with reading, is that it is very apparent that it is the lost human potential, the lost self-esteem…that is the most poignant. And, in the end it’s the most significant, because the loss in self-esteem is what leads to a whole host of social pathologies that are very difficult to look in the face. Crime, substance abuse, and the school drop out rate -any of those things – they are very difficult to face. And there is a line to be drawn between low literacy skills and those social pathologies.

There is a twenty-seven percent drop out rate of students with learning disabilities; that is more than twice the rate of the general population …lost human potential. And there are problems with substance abuse and juvenile justice problems. And certainly looking at the general population of students that drop out, one can go to prisons and see that it is very apparent the majority of inmates lack reading skill.

James Wendorf, Executive Director, National Center for Learning Disabilities. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wendorf.htm#TheRealCostisLostSelfEsteem

Preservation of Self-Concept

David Boulton: The work of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, in summarizing the reading research, seems to indicate that while there’s many different problems, there’s a spectrum of related problems involved here and that one of the first consequences, almost across the board to children who struggle with learning to read, is that they feel ashamed of themselves. They feel as if there is something wrong with them.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Part of the complex of reading failure is increasing frustration by individuals, children who are failing to read at their success in school and what school is all about. And it can in some cases, in desirable cases, resolve in greater motivation to try to get help and succeed. But in many cases it generates a sense on the child’s part of helplessness; helplessness not only with reading, but helplessness with school. You find those children turning to other avenues to gain reward to gain self satisfaction.

So, they don’t read well, so they don’t read. They may play a computer game because they’re better at that. So you find individuals shifting their activities into areas which they are getting a sense of satisfaction, a sense of reward, and away from activities that are frustrating, and that’s certainly the case for reading.

So, you see a pathway taken for children who are failing to read and it’s a way of preserving their self-concept of succeeding, but it’s a pathway that is not ultimately to their benefit because it takes them away from the activities from which they can derive knowledge and develop the skills that are important for success in school and in life.

David Boulton: At a somewhat more implicate level the emerging emotional sciences, with respect to ‘affect’ and its driving and directing influence over cognition, have suggested that we operate in a way that once shame gets to a certain threshold level we want to move away from it. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research studies are saying that children, because of the way we contextualize this whole reading experience, are feeling that there is something wrong with them because they can’t do this.

Again, we’re back to our beginning points: most of our children are to some degree in this space, for some degree of their education, feeling ashamed of how they’re learning. And if shame causes us to want to move away from what causes shame, then we want to move away from learning.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Yes, that’s certainly true. And we need solutions to this. We need curriculum solutions so that fewer children experience frustration and difficulty during the task of learning to read. We need to change the context of schooling so that the child who’s struggling in reading in third grade can have that problem addressed in a way that isn’t stigmatizing to the child and doesn’t generate the sense of shame. We need in some way to break out of the lock-step nature of elementary education so that if you don’t have what the other children have in first grade for some reason you are forever doomed and will never get the opportunities to pick up that information.

So, it is a very significant problem and the emotional and social consequences of reading failure are extremely important and are the soquali of the bad experiences that come from sitting down with text and not being able to figure out what’s going on, or not being able to figure out what’s going on at the level of one’s peers.

It’s often the implicit comparison with what other kids are doing in the classroom that generates not only the shame, but in some cases, the lack of motivation to do better. That is, if the overall expectations for that classroom, those children are low, then there’s no shame on anyone’s part with reading failure or low level reading success. The teacher isn’t ashamed, the school district isn’t ashamed and the state isn’t ashamed.

We need to create a context in which people understand that there is a problem, that they need to deal with it, but the child doesn’t experience shame for having not benefited from the type of instruction or societal support necessary.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#Shame

Difficulties in Reading Profoundly Undermine Self-Esteem

It’s hard to separate language from the development of self-esteem, self-worth and struggling at school. Although I’ve heard many parents say you know, ‘It’s such a frustrating problem: dyslexia or language learning problems because everyone looks at your child and thinks they’re fine. If they just worked a little harder they would be just fine.’ And yet you can see a child literally who started off being fine begin to wither on the vine as they begin to struggle at school and lose so much of their self esteem in the process.

So, this is a major problem. Not only is it a major problem for the long term economic development of the country – which of course is why I think there’s such a huge focus on literacy – but I think it’s also a huge problem for society to recognize the tremendous toll failure in school, which usually manifests itself earliest as failure learning to read, has on the development and the maintenance of self- esteem. on the sense of self of the individuals who have had difficulty learning to talk or learning to read or learning to communicate. Even when they have become successful adults, even doing very, very well, many times if you ask them about their earlier experiences you can still see the pain of that failure – the sense of failure has never left them.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#DifficultiesinReadingProfoundlyUnder

Ripple Effects of Reading Difficulty

I do see some very interesting ripple effects when kids are not acquiring reading skills. For example, it might be that a particular child in fourth grade is having difficulty keeping pace with reading comprehension or with decoding, and because he’s having trouble with reading, he hates to read. And when he does read, he gets almost nothing out of it because he’s reading very passively. And because he’s reading very passively, he’s not able to use reading as a way of building his language abilities.

So, what oddly happens is that his language problems caused his reading problems, and his reading problems are now causing much more aggravated language problems. Those language problems, in turn, are going to make it hard for him to follow directions, communicate well with other people, and even use language inside his mind for something called ‘verbal mediation.’ Verbal mediation is the process through with which you regulate your behavior and feelings by talking to yourself. And believe it or not, a lot of kids with language problems really don’t use language as a way of regulating themselves.

They get in trouble, they get depressed, because they don’t have a voice inside that says, ‘Yeah, I could take that medicine. I could take that drug from that kid, and hey I’m a cool dude. But oh, if I take it, I could like wreck my brain, and I could get addicted and my mother will kill me if she finds out, and I could get arrested.’ And all of that comes out of language, that sort of verbal conscience that’s guiding you.

So, if you go all the way back to the language problem and say, yeah, it’s causing a reading problem, and the reading problem is causing the language problem, and the language problem is causing a behavior problem, and the fact that this kid can’t read, and other people around him can read much better is eroding his self-esteem, making him feel pretty worthless.

Mel Levine, Professor of Pediatrics; Co-founder, All Kinds of Minds Institute; Director, University of North Carolina Clinical Center for the Study of Development and Learning; Author, A Mind at a Time, The Myth of Laziness and Ready or Not, Here Life Comes. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/levine.htm#NegativeCollateralEffects

Self-Esteem and the Affect of Shame

I think the low self-esteem, the sense of shame, is life-long. At the National Center for Learning Disabilities, we have a wonderful board of directors. We have at least two individuals on that board, both of whom have dyslexia and both of whom are former governors. They are extraordinarily accomplished individuals, both of them dyslexic. And both have talked at length about the continuing sense, not just of frustration or memories of failure, but precisely a sense of shame that is still remembered…classroom based, other children around, a teacher, not being able to do what other children seem to be able to do so easily. It stays for a lifetime.(More “shame stories”)

James Wendorf, Executive Director, National Center for Learning Disabilities. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wendorf.htm#SelfEsteemShame

Reading Consequences on Self-Esteem

This business of being unable to decipher what’s on the printed page has huge consequences for a child’s self esteem. That is the child’s general concept of who he or she is has huge consequences for how we see ourselves relative to our peers and forces us to defend against this bad feeling in a number of ways that I call the Compass of Shame.

Donald L. Nathanson. M.D., Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Jefferson Medical College, and founding Executive Director of the Silvan S. Tomkins Institute. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/nathanson.htm#DownwardSpiralShame

Lost Potential and Suffering from Self-Esteem Loss

David Boulton: I want to circle back to the self-esteem conversation because, in addition to the economic things, and as you said there’s this huge cost, from the child’s point of view, from the family’s point of view: it is suffering.

James Wendorf: Yes, well anyone who works with children who have learning disabilities confronts the issue of low self-esteem head on. By the time a child is usually identified with a problem in reading and the further identification is made that there is a learning disability…that child usually needs to be put back together in some way. There’s been failure, and usually over a long period of time. And usually by the time that special education services are provided or some other kinds of services are provided, the child needs some serious help with self-esteem.

Now we’ve actually looked into this at the National Center for Learning Disabilities. We’ve worked with researchers, and one of the best ways to address the self-esteem problem is through skill development. And children who actually are able to build their skills show an increase in self-esteem that is every bit as high as programs that might address their self esteem head on.

So by focusing on skill development, working on instructional issues, you can often bring the self-esteem up in the same way that might happen if a child were involved in some kind of social emotional development program that directly addresses the issue of self esteem.

David Boulton: Parenthetically, a good friend of mine, JohnVasconcellos, a State Senator in California, is one of self-esteem’s most visible proponents. He’s the one Gary Trudeau cartooned for creating the California Task Force to investigate the relationship between self-esteem and personal and social responsibility. Back in the 80’s his work brought self-esteem to national attention.

My own sense, based on engaging in dialogue with philosophers, scientists and researchers in that space, is that the issue isn’t self-esteem, rather what happens to children who learn to be self dis-esteeming. They learn to not trust, to not feel good about themselves. It’s an acquired shame.

James Wendorf: I think low self-esteem causes a child to pull back, to not engage. Why go out there and put yourself on the line if you know it’s going to be another failure and you’re going to be called on it either by your teacher or your classmates and you will be open to shame, to disapproval. Kids aren’t dumb; they know when something isn’t working and they know what’s going to hurt, so they pull back.

What children need is the experience of having success. That is what nourishes self-esteem. And success in building skills is one of the best ways to do it. When children have shown that they can actually master something and they have proof, they can point to it and they can be legitimately praised for it. That’s what works.

James Wendorf, Executive Director, National Center for Learning Disabilities. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wendorf.htm#LostPotentialalsoSuffering

Slow Readers Need More Time

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: What I say now is that dyslexia simply robs a person of time, accommodations like extra time return part of it, and that a person who is dyslexic has as much a physiologic need for extra time as a diabetic needs for insulin.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Now that we can show that with our brain imaging, that’s made an extraordinary difference. Because I’ve seen too many young people who were applying to graduate school or professional school who struggled their lives to reach the point where they can read accurately, but not automatically, are turned down for extra time. It’s like somebody climbing to the top of a mountain and you suddenly step on their fingers, and don’t let them take that last step, and knock them down. So, it may not sound like an important thing to you, but for all those people who have had difficulty reading it is.

David Boulton: All of these dimensions are critical. We’re looking at the family context, the social context, very particularly at the emotional affective context as well as the cognitive processing challenge.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s at the very — that’s at the heart.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s the heart and soul of it. Because you can teach a person to read, and you can do all the things, but if they’ve had that hurt and that pain and that blow to their self-esteem, that’s the most difficult. We have no medicine for that.

David Boulton: Yes. And it’s not just a bad feeling they’re having; it’s fundamentally processing-level debilitating, draining of the efficiency that’s necessary to process the thing that could make them feel better. It works in a downward spiral.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s right.

Sally Shaywitz, Pediatric Neuroscience, Yale University, Author of Overcoming Dyslexia. Source: COTC Phone Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shaywitz.htm#SlowReaders

Shame, Self-Esteem and Neuromodulation

David Boulton: Have you done anything to actually isolate shame, develop a kind of signature of what shame looks like when it’s triggered in the brain?

Dr. Michael Merzenich: No. I’ve thought about it primarily from the point and read about it primarily from the point of, you could say, it’s obverse; which is self-esteem or positive self-awareness or self-healing and haven’t really thought about it as you raise the issue. It’s a wonderful thing to think about in the obverse. I’ve primarily thought and read about it in a sense in another thing that would reflect it and that’s the sort of the ongoing loss of self-esteem, of self-confidence, or in terms of self-doubting and what can be done about it.

David Boulton: I spent a lot of time in the self-esteem world before getting into the reading world. I’m interested in the reading world because of what it’s doing to self-esteem. Although I don’t like the term self-esteem, it’s got a lot of baggage with it.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: It does and it’s confusing.

David Boulton: I think of it as a buoyant absence of self-negativity rather than a positive accumulation….

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, exactly.You can have a boy that’s very self-confident, and yet in a sense, identifies himself in a broad domain as a failure and, in fact, his self-confidence is a kind of compensation. Actually, what I’ve really been interested in is the origins of bad conduct behavior because I think it would be a tremendously positive thing if we could understand it. Again, it relates to the development of emotional control and these complex reactions that occur in the brain that govern, in this overriding way, the general behavior of a child.

David Boulton: The sum of our view is this… We think that children are being overwhelmed with a form of confusion that is unnatural to them and they are learning to associate the feeling of that confusion with shame. We are all shame avoiders, escape artists; we don’t like to feel shame. So just as reading involves an assembly that’s faster than conscious, there’s a faster than conscious aversion to shame which is associated with feeling certain kinds of confusion, which in turn decapitates learning because learning involves extending through confusion.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: I love that description, although I don’t really understand its neurology. I love the description.

David Boulton: One of the things we’re trying to do is bring about some new explorations into the effects of negative affect triggering in the stream of cognitive processing. It seems to me it’s got to be dis-entraining.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, right. I think it’d be a great leap if you could understand that. I mean, if you have a child that enters school and the child fails at school,which means that they’re experiencing, they’re reacting in these ways to it and if they’re misbehaving, they have about an even money chance later in life to commit a felony. I mean the simple fact is we have to figure out how to get to those kids more reliably and more completely and it doesn’t necessarily involve cultural re-education. The more deeply we understand the neurology the more we could understand how to drive true correction of it.

David Boulton: Unless the neurology work embraces and includes the interdynamics between the more mechanically cognitive processes and the affectual processes that are orienting, contextualizing, powering, the cognitive activity, I don’t see how we can get there.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Well, I don’t know. I believe all these things are at some level accessible. Whether they could be, whether such training could be easily incorporated under conditions of something like a public school where an aspect of the training might include some level of social training, whether that’s really necessary or not, I don’t know.

David Boulton: Well, it’s also a matter of re-contextualizing the kinds of challenges that most trouble children so that they are less provoking of shame.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Well, one of the ways we’ve tried to design the software that we’ve applied to children, the training programs we provide to children, is to absolutely ensure a high level of success in every kid and this is a big part of it. A big part of it is to find ways in the course of every kid in a significant part of their life and day to ensure that they succeed in things. I mean one of the magic things that has to happen to every kid is they have to find something, something that they’re good at and everybody acknowledges and everybody tells them and they tell themselves. As long as you have enough of those things happening in your young life you can accept the things someone else is better than you at.

David Boulton: And the danger there is that it can be that the thing that I feel good about myself is that I can beat up everybody around me, right?

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, I mean there is that. There has to be things outside of that realm.

David Boulton: All right. I think we’ve talked about many of the things we’re both most interested in. Is there anything that we’ve inspired in the course of our conversation, anything you’d like to touch on that we haven’t yet?

Dr. Michael Merzenich:Only to say that, this is a great quest. There is great hope that we can progress in understanding the neurological origins of things like this and the crucial dimensions as you’ve expressed, in this relationship between the emotional side of life and the overriding behavioral things that relate to neuromodulatory control in emotion.

I mean when you talk about neuromodulators and you talk about the things that condition learning, you’re also talking about the overlay of emotional baggage that comes with them, that are expressed with them, but also derive from them. You also talked about the fact that each one of us is basically creating the complex conditions under which they are constructed and they are inhabiting our heads and controlling our behaviors in our life.

One of the crucial things is to understand this complicated interplay between these modulators and understand how they evolve – how plastic they are. That’s been studied almost not at all. People have studied the axis of neuromodulation. Dopamine cells and dopamine chemistry has been manipulated in hundreds of ways partly because people see that there’s profit in it – to manipulate it because it’s so clearly involved in so much malfunction and so much disease in psychiatry and neurology. But still almost nobody has studied in any detail, or in any intelligent way, how this capacity, how this control, how this incredibly differentiated nuances of emotional control, as they influence learning and behavior are actually created and developed in an individual way and in an individual person. There’s high stakes in such understanding.

So, one of the things I think is evolving or will gradually evolve is a level of science in that area that will parallel the level of science in learning as it relates to the sort of dry side of learning, and that’s skill learning. As that evolves I think we’re going to generate more and more powerful ways to intervene in real human problems.

David Boulton: That’s excellent and that’s being echoed in other circles. Russ Whitehurst realizes that it is a weakness in the whole assessment paradigms of education. Other scientists that we’re talking to are also recognizing that this is a huge lacuna in our overall understanding and that it’s too significant to leave out of the equation.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, and not just for kids. It’s a big part of what we’re trying to do with older individuals. I mean with a seventy, eighty or ninety year old this machinery is now falling apart and you have to think about how you can reinvigorate it, revitalize it, re-enrich it. You know, we have to. People’s attitudes can be better. There are things that are rewarding to them and can be made stronger and more elaborate and they should be. It’s part of being healthier and happier in older age. And guess what emerges when you get older? Shame. What emerges is a lack of confidence. I’m now worried about whether I can succeed, whether I can keep my end up. I mean all of these things enter in again in spades.

David Boulton: That’s why I think it’s so important that we understand that there is a biological basis for the core affects and that shame seems to be, when we think about the human animal, a fundamental learning prompt, a really great thing. But if we become averse to the feeling of shame before it actually bubbles up, before we can think about it, it’s steering us away from what we need to learn about.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Absolutely.

David Boulton: And it seems to be happening on a grand scale.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, right. It just basically shuts you down.

Michael Merzenich, Chair of Otolaryngology at the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences at the University of California at San Francisco. He is a scientist and educator, and found of Scientific Learning Corporation and Posit Science Corporation. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/merzenich.htm#ShameSelf-EsteemandNeuromodulation