Public Reading Shame

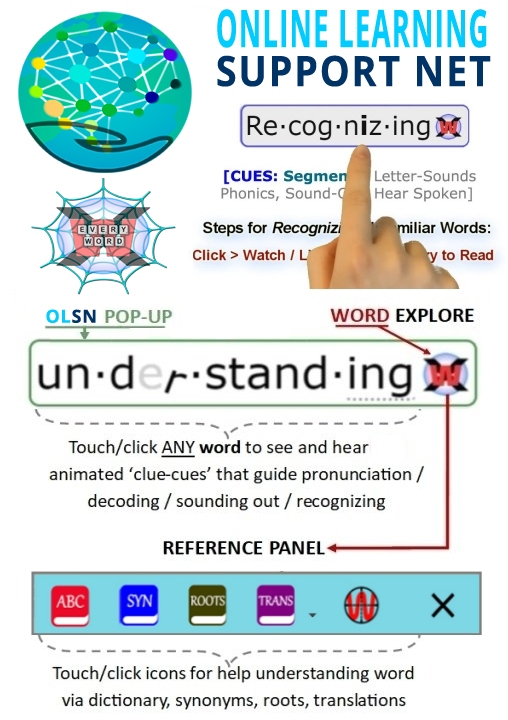

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Shame

Typically, from first through third grades there is a lot of oral reading, and there are interactions where the kids are expected to read out loud, orally or in round robin. When kids are hesitant, disfluent, inaccurate, slow and labored in reading, that is very visible to their peers and remember the peers, the other kids, again look at reading as a proxy for intelligence. It doesn’t matter if this kid is already a genius and can do algebra in the second grade, reading produces particular perceptions. Better said, lousy reading produces a perception of stupidity and dumbness to peers and clearly to the youngster who is struggling. That is the shame. There are very visible differences between kids who are doing well with print and youngsters who are struggling with print. They feel like they’re failures; they tell us that. (More “shame stories”)

G. Reid Lyon, Past- Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Current senior vice president for research and evaluation with Best Associates. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lyon.htm#ShameAvoidance

Multiplication Effect of Shame

So, in the classroom situation there’s a multiplication effect. The more trouble any individual has reading in a classroom situation, the more likely that child is to have further shame affect interruption of the normal interest in reading. Immediately downstream what do we have? We see kids who simply say I don’t want to read. I don’t want to try because every time I try in class I’m going to feel worse. I’m not going get rewarded like Francine or Billy, I’m going to get laughed at and that hurts.

So, first the shame comes from being unable to decipher the code. Then there’s the shame that comes because you did it in public. And then there’s the next level of multiplication of shame experience; that the other kids will compare you to them and they feel better than you for that moment and your position in class is reduced tremendously. That means the simple failure to figure out what the letters mean on the printed page has not only become difficult for you to understand yourself, but it’s placed you in a position relative to your peers where you are defined by them as lesser and it’s acceptable to laugh at you and deride you for this inability to read.

If you’re reading one-on-one with a parent, a loving tutor, an older sibling who’s helping you and you feel safe, then that moment of shame is not magnified as it is in the classroom situation. So, when tutoring one-on-one, the nature of shame is that we feel less dangerously exposed if we feel loved. It’s merely exposure. But when we’re in the atmosphere of the classroom where every other child in that classroom is at risk of feeling exposed and compared invidiously to every other kid, then an error I make in reading reduces me in everybody’s eyes and I’m better off not trying.

Donald L. Nathanson. M.D., Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Jefferson Medical College, and founding Executive Director of the Silvan S. Tomkins Institute. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/nathanson.htm#MultiplicationEffect

Shame

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Part of the complex of reading failure is increasing frustration by individuals, children who are failing to read at their success in school and what school is all about. It can in some cases, in desirable cases, resolve in greater motivation to try to get help and succeed. But in many cases it generates a sense on the child’s part of helplessness; helplessness not only with reading, but helplessness with school. You find those children turning to other avenues to gain reward to gain self satisfaction.

So, they don’t read well, so they don’t read. They may play a computer game because they’re better at that. So, you find individuals shifting their activities into areas which they are getting a sense of satisfaction, a sense of reward, and away from activities that are frustrating, and that’s certainly the case for reading.

You see a pathway taken for children who are failing to read and it’s a way of preserving their self-concept of succeeding, but it’s a pathway that is not ultimately to their benefit because it takes them away from the activities from which they can derive knowledge and develop the skills that are important for success in school and in life.

David Boulton: At a somewhat more implicate level the emerging emotional sciences, with respect to ‘affect’ and its driving and directing influence over cognition, have suggested that we operate in a way that once shame gets to a certain threshold level we want to move away from it. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research studies are saying that children, because of the way we contextualize this whole reading experience, are feeling that there is something wrong with them because they can’t do this.

Again, we’re back to our beginning points: most of our children are to some degree in this space, for some degree of their education, feeling ashamed of how they’re learning. And if shame causes us to want to move away from what causes shame, then we want to move away from learning.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Yes, that’s certainly true. And we need solutions to this. We need curriculum solutions so that fewer children experience frustration and difficulty during the task of learning to read. We need to change the context of schooling so that the child who’s struggling in reading in third grade can have that problem addressed in a way that isn’t stigmatizing to the child and doesn’t generate the sense of shame. We need in some way to break out of the lock-step nature of elementary education so that if you don’t have what the other children have in first grade for some reason you are forever doomed and will never get the opportunities to pick up that information.

It is a very significant problem and the emotional and social consequences of reading failure are extremely important and are the soquali of the bad experiences that come from sitting down with text and not being able to figure out what’s going on, or not being able to figure out what’s going on at the level of one’s peers.

It’s often the implicit comparison with what other kids are doing in the classroom that generates not only the shame, but in some cases, the lack of motivation to do better. That is, if the overall expectations for that classroom, those children are low, then there’s no shame on anyone’s part with reading failure or low level reading success. The teacher isn’t ashamed, the school district isn’t ashamed and the state isn’t ashamed.

We need to create a context in which people understand that there is a problem, that they need to deal with it, but the child doesn’t experience shame for having not benefited from the type of instruction or societal support necessary.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#Shame

Reading Aloud in Class

David Boulton: Yes. One of our interests is to explore what happens when children become so ashamed of how they feel about themselves in this process that it creates an almost preconscious aversion to it.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Well, I think that’s true. I’ve had the good fortune to speak to many people who are dyslexic, and who’ve been highly successful by anyone’s standards. But if you speak to them, as I have, and you ask them: “Well, what was it like for you when you were a child, particularly, what was school like?” And you see this terrible look on their face. Particularly they recall the really horrible experience of being called upon to read aloud in class, in front of everyone when they couldn’t do it.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s the kind of mental image and emotional experience that stays with a child. It’s really remarkable how many adults will remember that and can picture that classroom and how they felt and how they wanted to get out of there and avoid that at all costs.

David Boulton: Right. Almost everyone we talk to speaks about this feeling level connection with people who are suffering with this challenge.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Yes, this isn’t an academic abstraction, it’s about real people who have to live with something that people don’t see, and that’s why I guess it’s been a really wonderful thing that the science has progressed so far, and that we actually now have the ability to see the brain at work, so we can actually see what is happening at the most basic levels.

Sally Shaywitz, Pediatric Neuroscience, Yale University; Author, Overcoming Dyslexia. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shaywitz.htm#PointofView